The Impact of the CHS on US Higher Education

Tom Arcaro, a professor of sociology at Elon University, North Carolina, tells us about his experience in adopting the Core Humanitarian Standard (CHS) in US higher education.

The impact of the CHS on US higher education

Social action of all types tends to have both intended and unintended consequences, and the development of the Core Humanitarian Standard (CHS) is a good example of a very positive, though unplanned, impact on US higher education. Below I detail the impact of the CHS on a program at my home academic institution and a national conversation about these standards. My main point below is that the CHS can – and should – be used outside the humanitarian field, especially in the higher education sector. The CHS helps Elon University insure that our global partnering efforts remain ethical and culturally appropriate. Our adoption of the CHS is a practice which I am encouraging among my colleagues, both at Elon and throughout US higher education, beginning with the consortium of colleges and universities banded together under Project Pericles.

Assessment-worthy pledges and partnerships

In 2002 I founded the Periclean Scholars program at Elon University in North Carolina, accepting the challenge to raise the level of civic engagement and social responsibility of the entire university community. Although service learning[1] and community engagement are well established in US higher education, the Periclean Scholars program is unique, as it is a multidisciplinary, cohort-based, three-year academic service-learning mentorship program that operates in accordance with the CHS commitments.

Our ‘Periclean Pledge’ serves as a de facto mission statement for the program. Over the years, as we became more attuned to the serious responsibilities inherent in partnering with people and organisations in our countries of focus, such as Haiti, India, Namibia and Zambia, to name only a few, we felt the necessity to deepen our Pledge, to give it more meaning, purpose and focus, with an emphasis on assessment criteria. For years the Pledge consisted of six statements – related and meaningful, but bare statements with little depth. Taking a cue from the CHS we set about the task of re-crafting the Pledge using, with permission, the layout and the structure provided by the CHS. We had to ask ourselves exactly what the Quality Criterion was for each Pledge statement and then go even deeper and be more specific by adding Key Actions for each. This process of deepening the Pledge was a useful exercise and gave us pause to consider each statement in light of more practical ‘assessment-worthy’ terms. Thus, overall, we could say that the CHS was used as a template, a set of best practices to create a measurable Pledge that we can use as a point of reference to assess the quality and accountability of our work.

In addition, we made the decision to put the CHS into the syllabi of our Periclean classes. Each cohort of scholars, consisting of 25 to 30 people, is assigned a country of focus and then charged with partnering with people and organisations in that nation to address social and/or environmental issues. Each cohort must first spend time learning about their country – its culture, history, politics etc. – and then develop a plan to address some aspect of their chosen issue, typically in a ‘service-learning’ context. When it comes to partnering, the CHS is used to identify the most appropriate organisations. A good example to demonstrate our commitment to the CHS is the class of 2016, who spent considerable energy researching a small NGO working in Honduras and ultimately withdrew support because this organisation did not clearly adhere to some of the CHS guidelines. All cohorts consider an array of partnering possibilities and use exhaustive research and questioning to finally decide on a path forward.

Although the CHS has provided a wonderfully comprehensive model that will insure the highest standards for our program, our students encounter some difficulties retrofitting these standards to their smaller class project’s scope: They find that the heavier focus on aid as opposed to development in the CHS runs counter to their typical partnerships which tend be more development oriented. Furthermore, as the Standard and the accompanying materials were developed for the humanitarian sector our students often feel overwhelmed by the concept and the technical information provided. The CHS can be difficult to fully comprehend for students with little background, just getting familiar with the sector. As faculty, our primary mission must remain educating undergraduates in the most effective manner possible, and for this end it would be useful to have a guide which helps structured learning and contains examples of learning modules that build on each other. For example, the first module could cover the history and the development of the Standard, the second the rationale behind the commitments, the third the key actions, etc. This would facilitate deeper understanding of the CHS and thus later contribute to its further development. Perhaps educators themselves could be asked to populate a small section of the CHS Alliance website with some teaching examples, curriculum suggestions, and best practices, and in the future be invited to consult on a regular basis as the next iteration of the CHS gets discussed.[2]

Guidelines for the Higher Education Sector

Community engagement in the form of internships, volunteerism and other forms of curriculum-based service-learning has been part of American higher education for at least a century, having been embedded into the founding mission statements of most faith- based (especially Jesuit) and historically black colleges and universities (HBCU’s). At Elon, like many private, predominately white liberal arts colleges and universities, the service-learning community engagement tsunami began to accelerate in the late 1980s and has been building momentum ever since. Many individual programs, departments, and schools have established clear ethical guidelines as well, these tending to be idiosyncratic to the specific curricular initiatives involving engagement off campus.

Seeing that the US higher education lacks a sector-wide approach to address the ethical consideration of these community and service-based learning programs, I turned to the CHS as an existing good practice for the humanitarian sector.

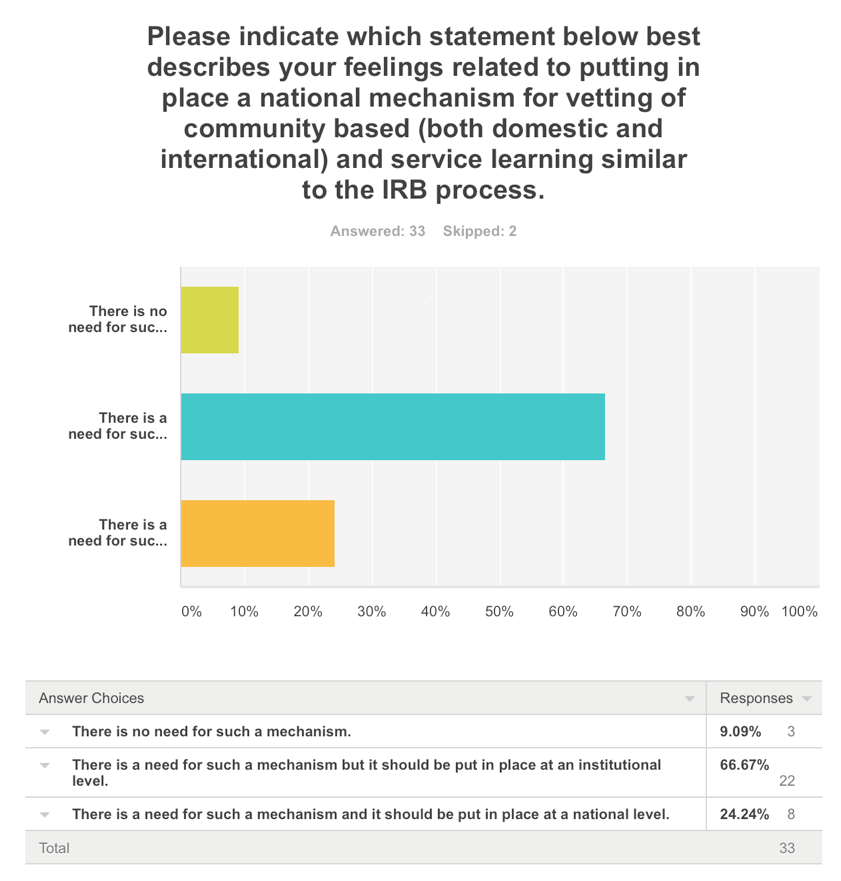

I have talked about this idea with the head of Campus Compact in North Carolina, the leadership of Project Pericles, my direct counterparts at many Periclean institutions, as well as colleagues in Denmark, Sweden and the UK, and colleagues here at Elon. All embrace the idea of at least moving the conversation forward to the next phase. In January of this year I administered a short exploratory survey to my co-directors, and most were in favour of having at least institution-wide policies in place. In follow-up conversations it has become clear that a CHS-like set of guidelines is worth serious consideration though there is some hesitation regarding embracing a “sector-wide” set of guidelnes.

There is a growing effort within the business world to establish a unified code of ethics as well. The B Corp movement, begun in the United States, has gained traction, being, in substance, currently replicated in Italy and Australia. These principles are emphasized in both undergraduate and graduate business degree programs in many US colleges and universities, including here at Elon.

Recommendations for employing CHS in other sectors

From the critical outsider’s perspective ‘do-goodery’, be it in the guise of academic community engagement programs, CSR (corporate social responsibility) initiatives or from the more traditional humanitarian aid sector, must proceed from a ‘first, do no harm’ perspective. The CHS has provided a deeply meaningful and provocative model for other sectors to emulate.

My suggestion is that in the short-term the CHS should be adapted and then adopted, both within higher education and in the corporate world. In the longer-term each sector should come together – just as all stakeholders did yielding the CHS – and establish equally thoughtful and thorough standards of their own.

[1] Service learning is, for example, having the student serve in the community (locally or globally) doing volunteer work, etc., and rigously processing the experience with the student through the lens of course material.

[2] As of June 1, 2017 I have transitioned out of my position directing the Periclean Scholars program. The new director, himself a class mentor, supports and has facilitated the use of the CHS into the future.